Synthography: a definition of the medium

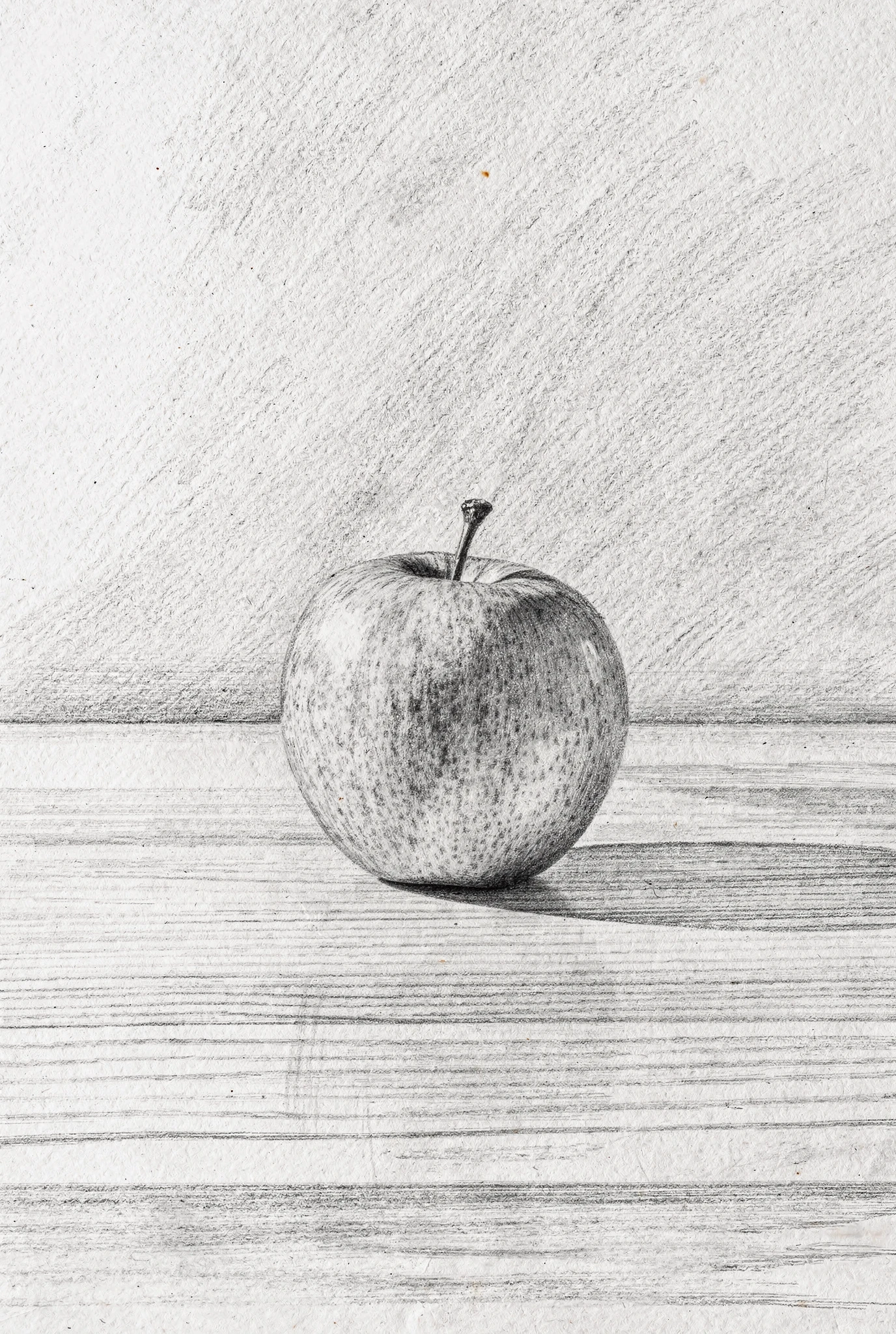

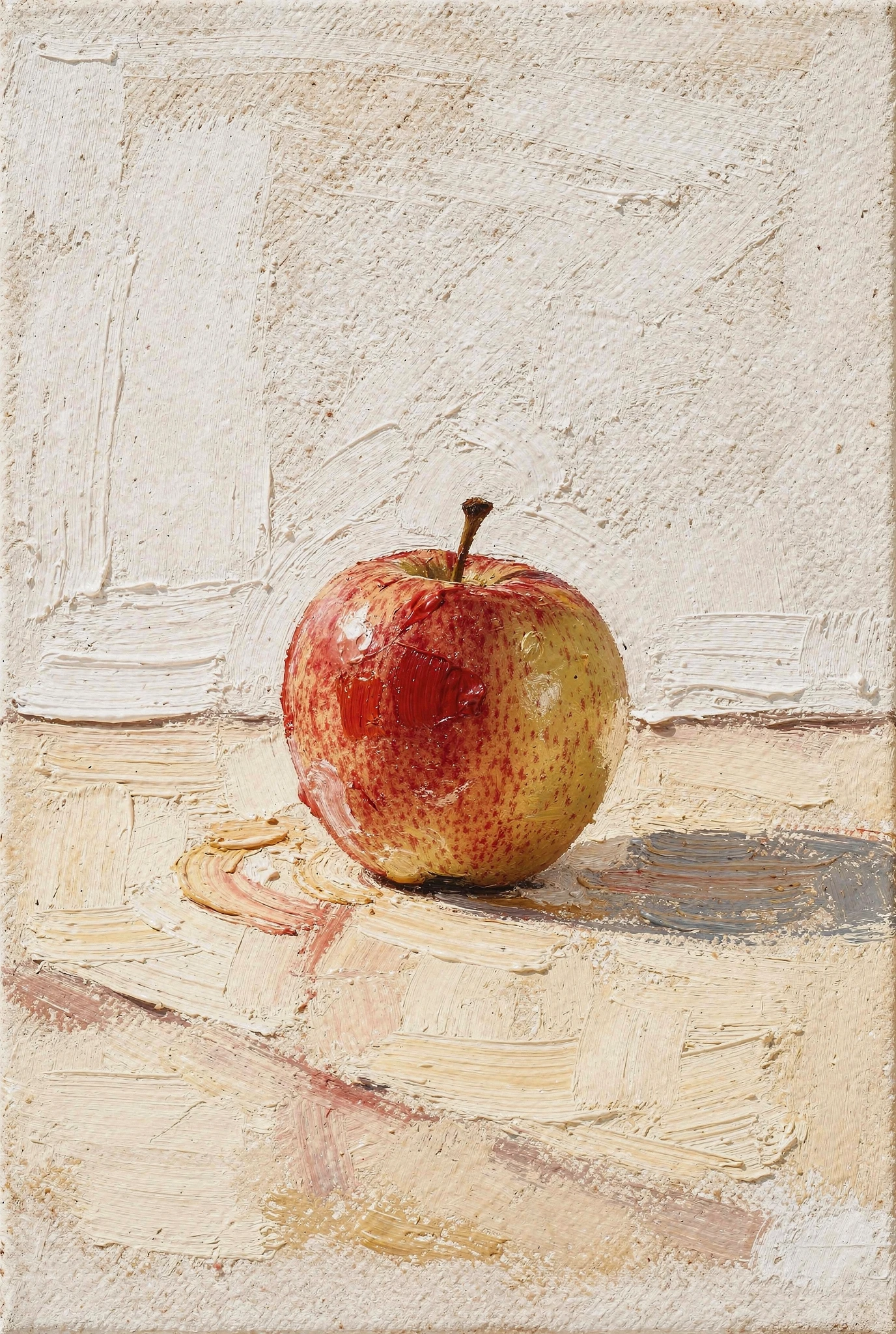

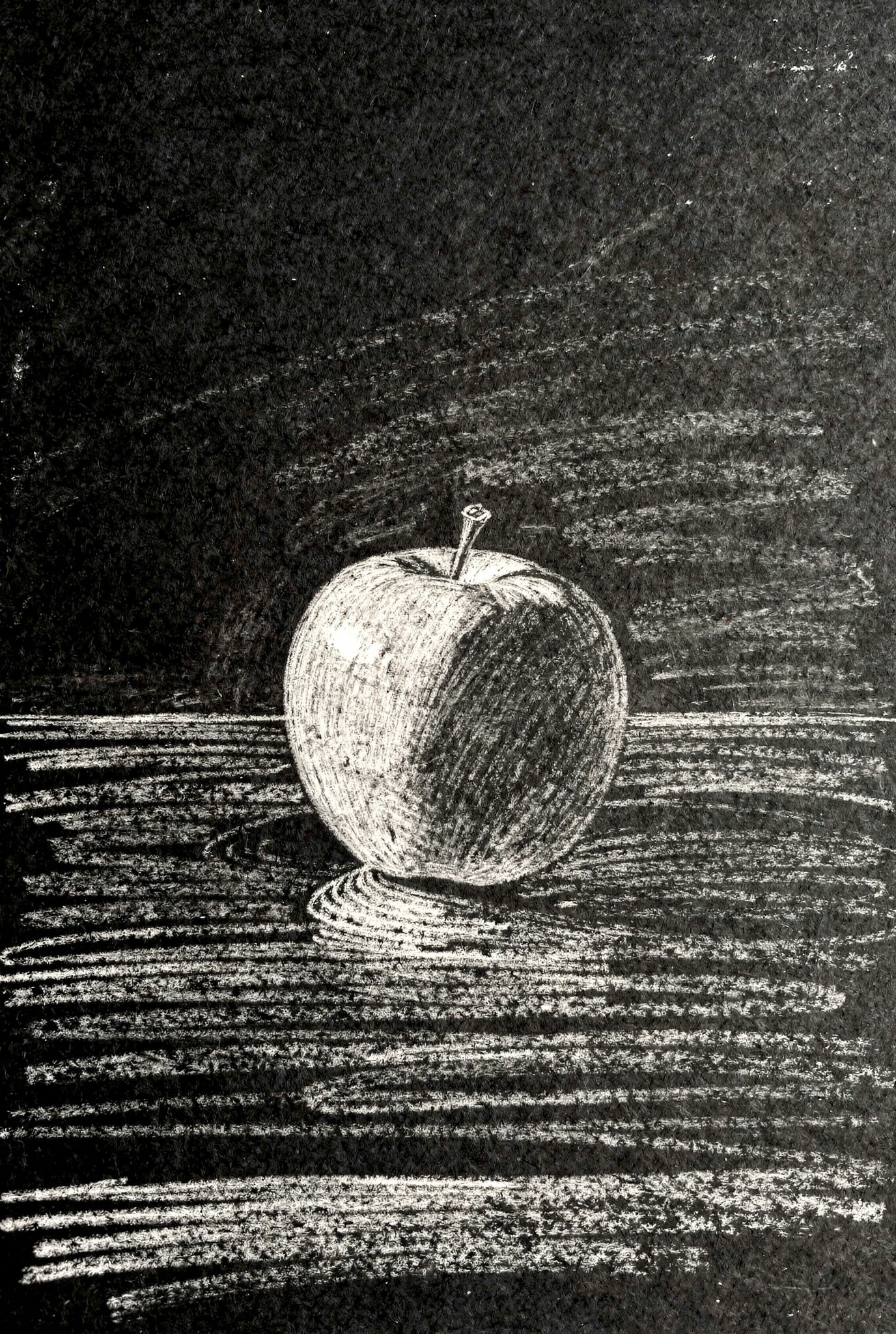

Apples carry a lot of baggage. There is the apple in the Garden of Eden (temptation, knowledge, trouble); the poisoned apple in Snow White (beauty, vanity, collapse); Cézanne's apples (form, repetition, the slow dismantling of painting itself). There is the Big Apple, and there is Apple™ — a logo, a company, a device in your pocket. There are thousands of apple varieties worldwide, yet most of us encounter only a small handful in UK supermarkets. They are familiar, neutral, quietly perfect. We recognise them without thinking, which is precisely why apples are useful here. Because these are not apples. And these are not photographs. What you are looking at are synthographs — images constructed using generative artificial intelligence. No camera. No fruit bowl. No light bouncing off real apples. Just language, probability, and intention, assembled into images that behave like photographs. If they look convincing, that is the point. If they look boring, even better. Sometimes the most radical thing an image can do is sit calmly and refuse to announce itself. Synthography is a form of image-making that uses generative artificial intelligence to construct images rather than capture them. Like photography, it produces images that can appear convincingly real. Unlike photography, it does not record light from the world, nor does it document an event or a moment in time. Instead, it assembles images through synthesis — combining patterns, probabilities, and language into visual form. In simple terms, a synthographic image is not taken; it is written into being. It begins not with a camera or a subject, but with intention, articulated through language, structure, and constraint.

The word synthography follows the same linguistic structure as photography. Where photography derives from the Greek phōs (light) and graphein (to write or inscribe), synthography replaces light with synthesis. It is image-making through composition rather than exposure: writing with constructed possibility instead of recording illumination. The result may resemble a photograph — sometimes uncannily so — but its relationship to reality is fundamentally different. A photograph is indexical: it bears a physical trace of something that occurred. A synthograph does not. It is not evidence, nor a record of presence. It is a convincing fiction, designed to behave like an image we recognise while remaining untethered from the world it appears to depict. This distinction becomes clearer when compared with illustration and painting. Illustration is an act of direct translation: an image is intentionally drawn, painted, or rendered through deliberate mark-making. Even when mediated by software, the illustrator or painter constructs form through gesture, stroke, and explicit visual decisions, working materially against a surface. In synthography, the artist does not execute the image piece by piece. Instead, they define the conditions under which an image may emerge. Language initiates the process, systems generate possibilities, and the artist responds — selecting, refining, redirecting, or refusing outcomes. For this reason, synthography is sometimes described as painting with words: not because it resembles painting materially, but because it shares a similar posture of indirect control, where intention shapes form without dictating it outright. The image is not executed; it is negotiated.

What a synthographic image resolves from is not a scene, an object, or a memory, but a latent space: an abstract field shaped by patterns learned from training data drawn from vast numbers of images. This space does not contain pictures as such, but compressed visual possibilities — tendencies, correlations, and statistical relationships without fixed referents. When an image is generated, it emerges gradually, as structured noise resolves into form under conditions set by language and probability. The image feels photographic because it inherits the visual grammar of photography, yet it depicts nothing that has ever existed. What becomes visible is not a captured moment, but a probability made legible. In practice, synthography most often begins as text-to-image: written language used to initiate an image. From there, images are refined through selection and iteration, sometimes guided by existing images in image-to-image workflows or reference-based processes that steer composition, material, or tone. These approaches form a continuum of control rather than discrete stages, allowing the artist to move between broad instruction and precise adjustment. The tools vary — including systems such as DALL·E, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, and Flux — but the underlying principle remains constant: language initiates possibility; judgement shapes outcome. For this reason, "AI art" is an imprecise label. It names a technology rather than a practice. Synthography instead names a specific image-making medium, defined by process, decision-making, and intent.

Synthography is collaborative by nature, but it is not automated. The machine generates images without understanding meaning, coherence, context, or restraint. Those responsibilities remain human. The artist works through writing prompts, setting parameters, refining direction, and evaluating results. Authorship resides in selection, refusal, iteration, and curation. This distinguishes synthography from novelty-driven generation or one-click production. Like photography or printmaking, it rewards patience and discipline. Images are tested, rejected, adjusted, and contextualised; series are constructed over time rather than accumulated. Generative image-making did not appear overnight. It developed gradually through decades of research in computer vision, procedural art, neural networks, and machine learning, long before it entered public awareness. What has changed in recent years is not the existence of generative systems, but their accessibility and visual fluency. The current moment marks a point of maturity, where image synthesis has become stable enough to support sustained artistic practice rather than isolated experimentation. As a result, synthography is already in active use across the creative industries — in fashion, advertising, editorial, and brand-led image-making — where precision, consistency, and cultural literacy matter as much as visual impact. In these contexts, generative AI functions not as an autonomous artist, but as a studio instrument. In this sense, synthography can be understood as a form of digital alchemy: where alchemists once sought to turn base matter into gold, synthography transforms words into images.

Gallery

"The image is not the thing." — René Magritte