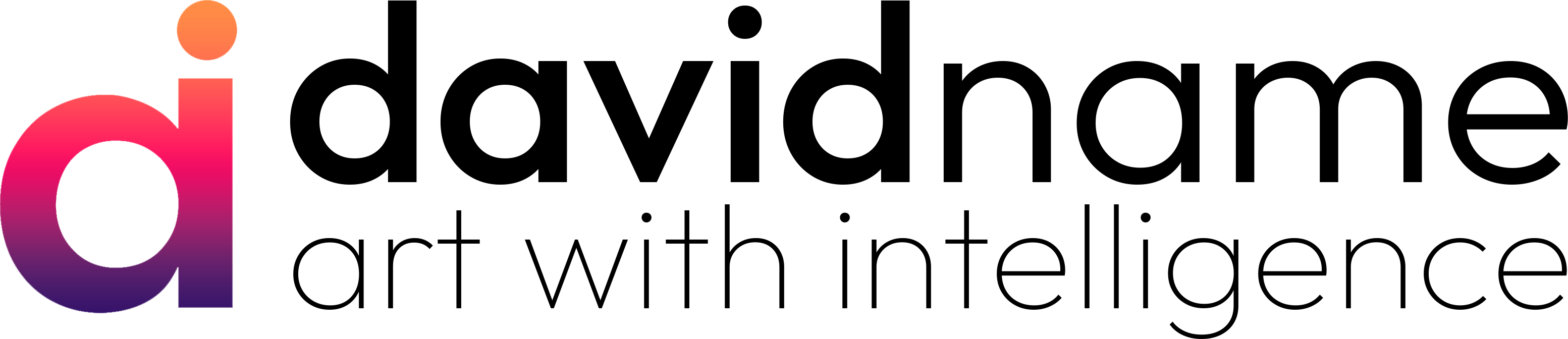

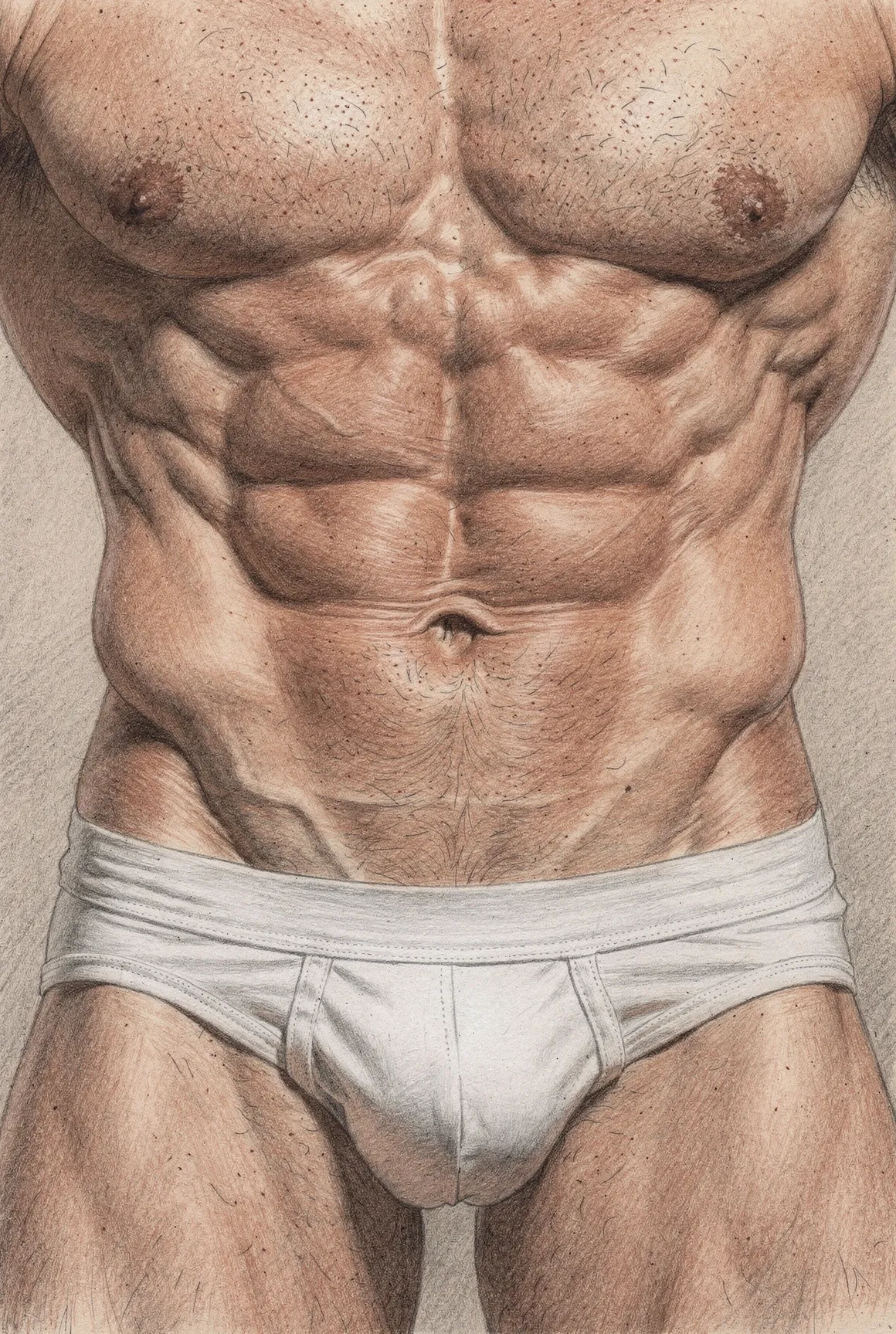

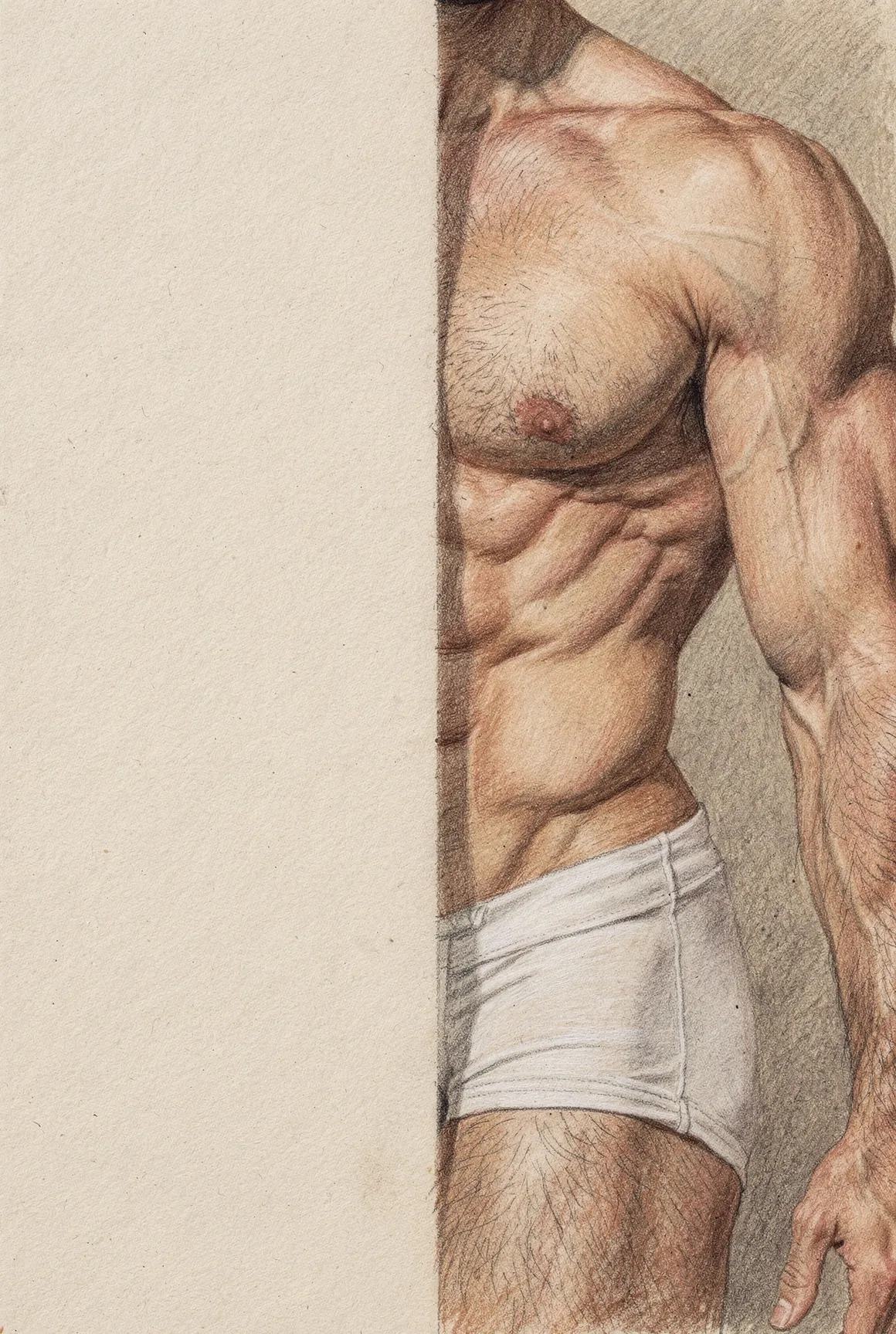

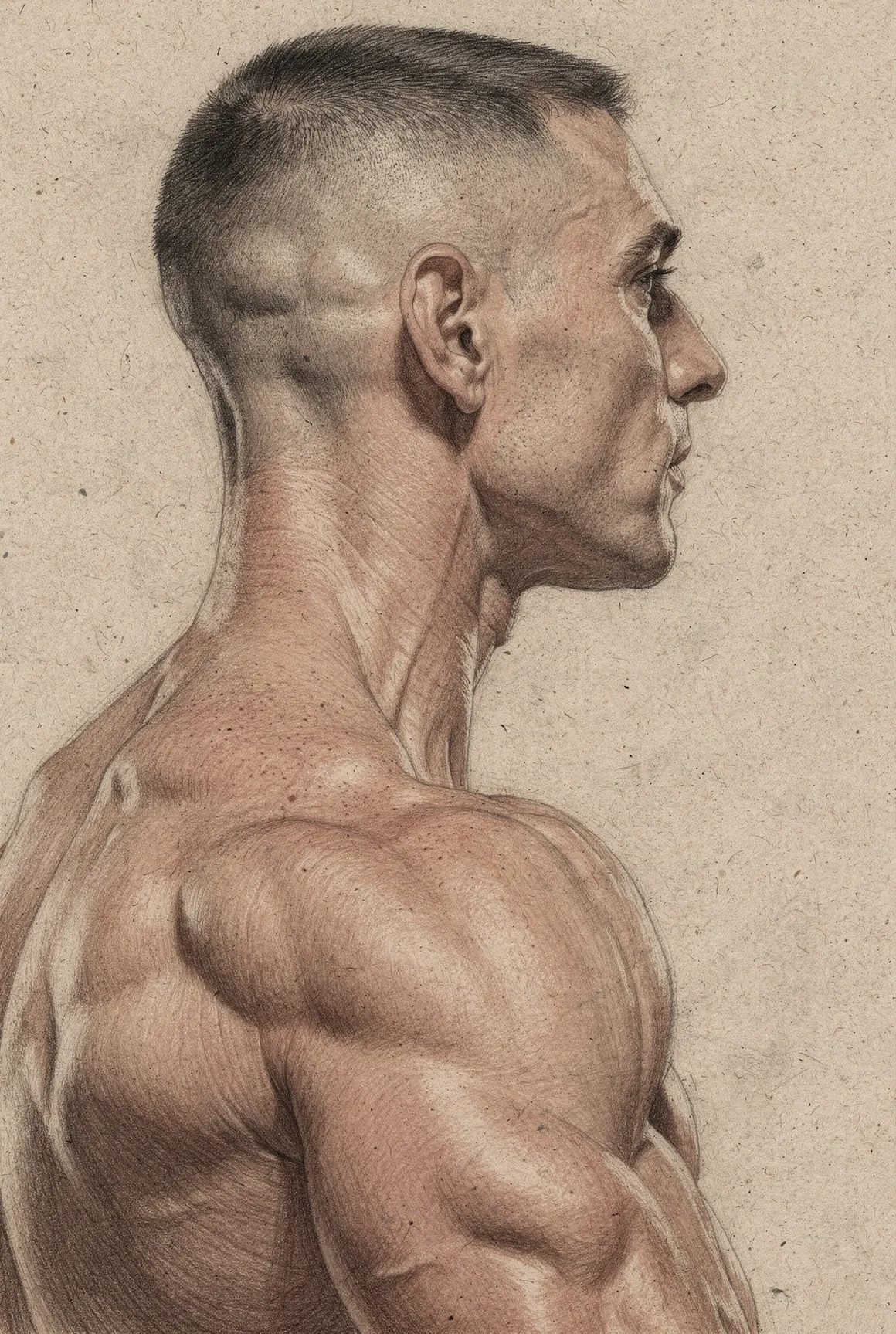

Corpus: the physical body

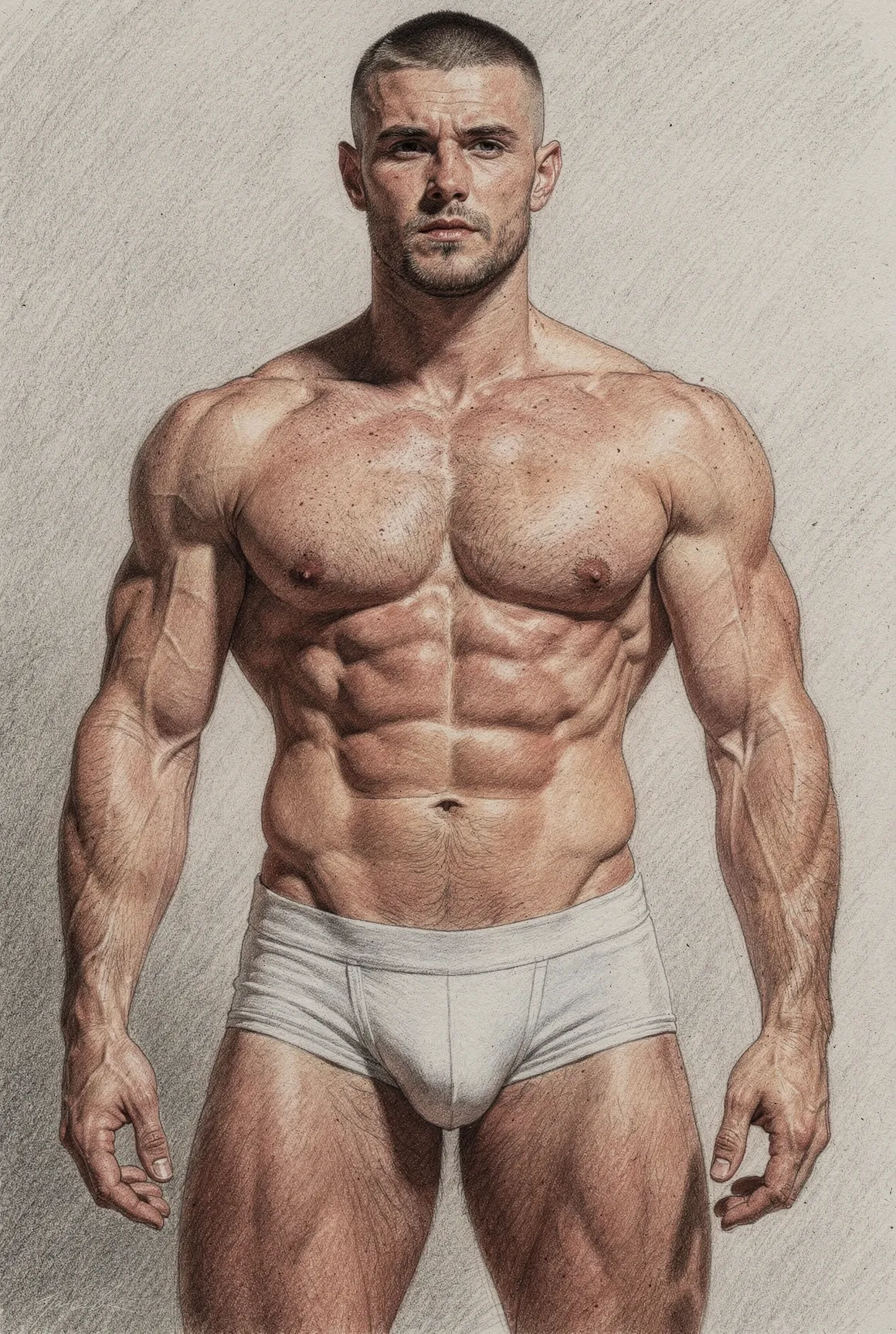

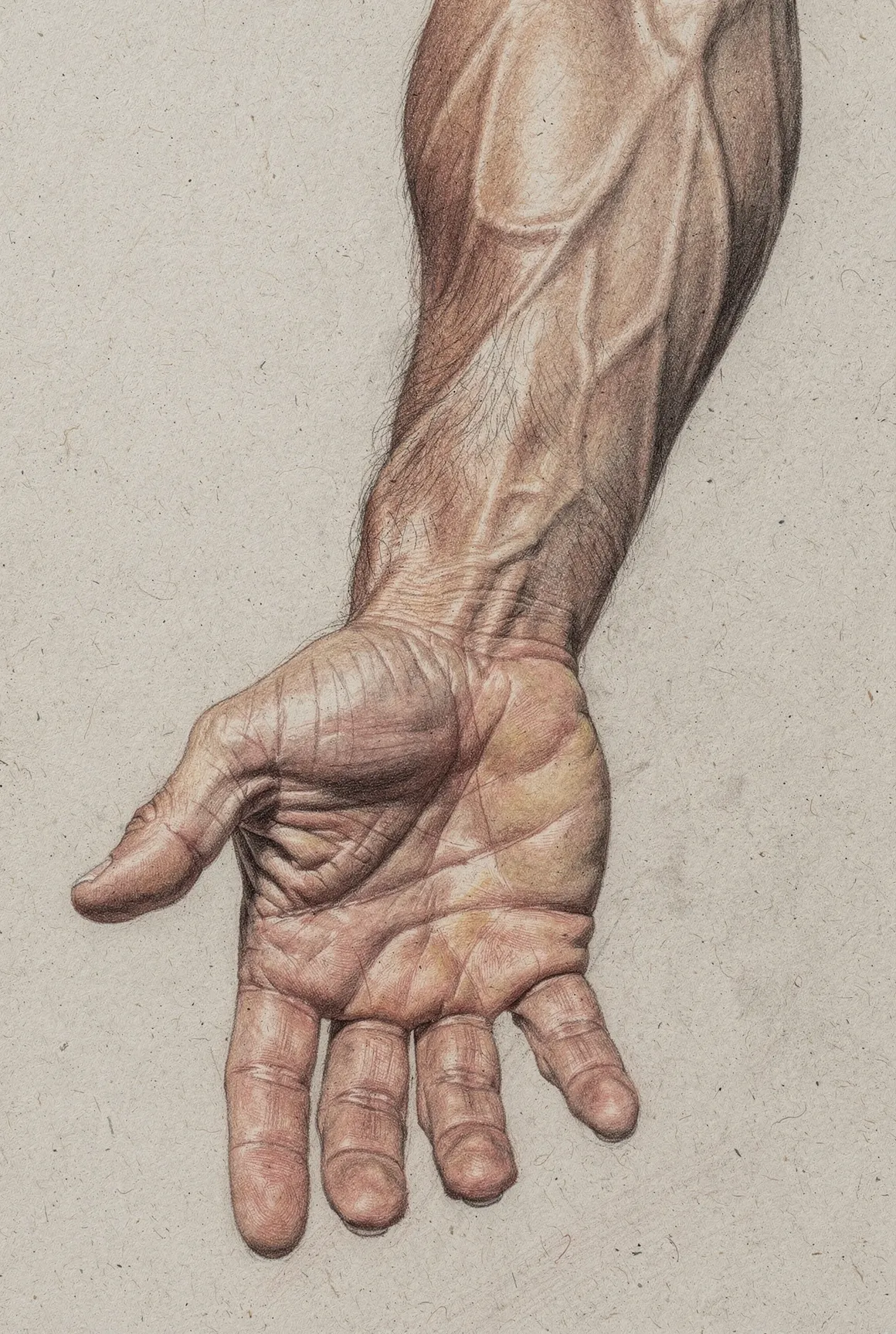

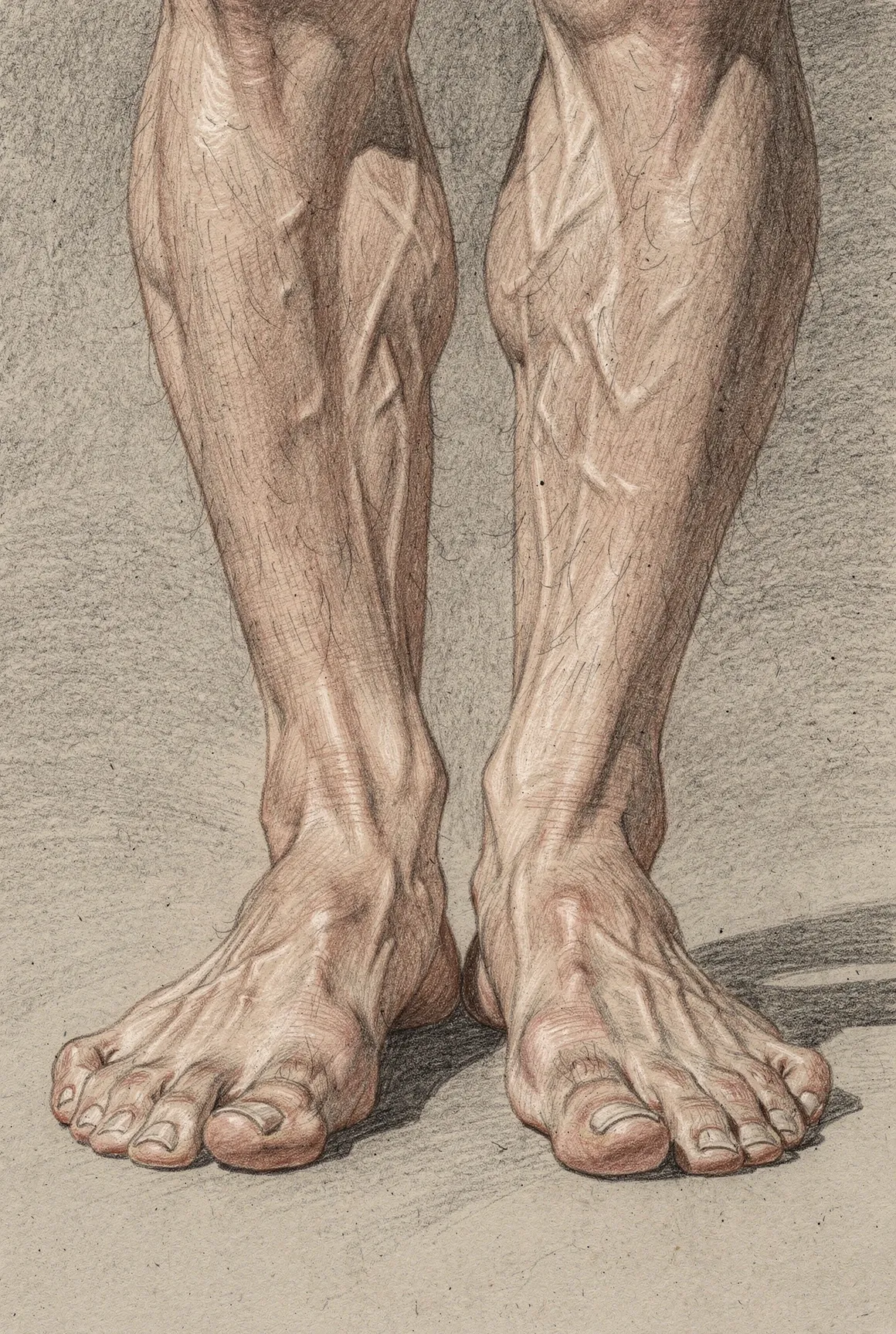

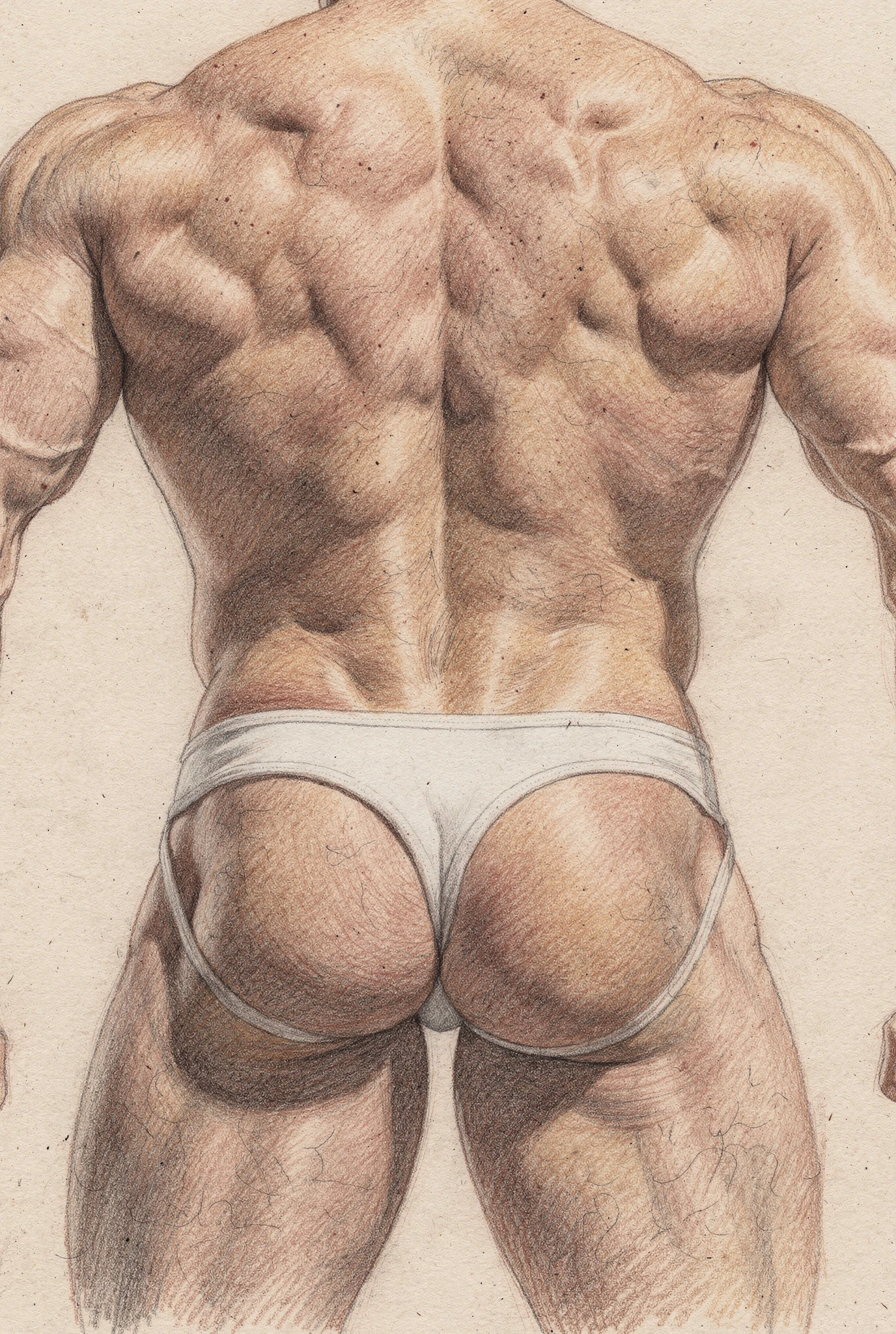

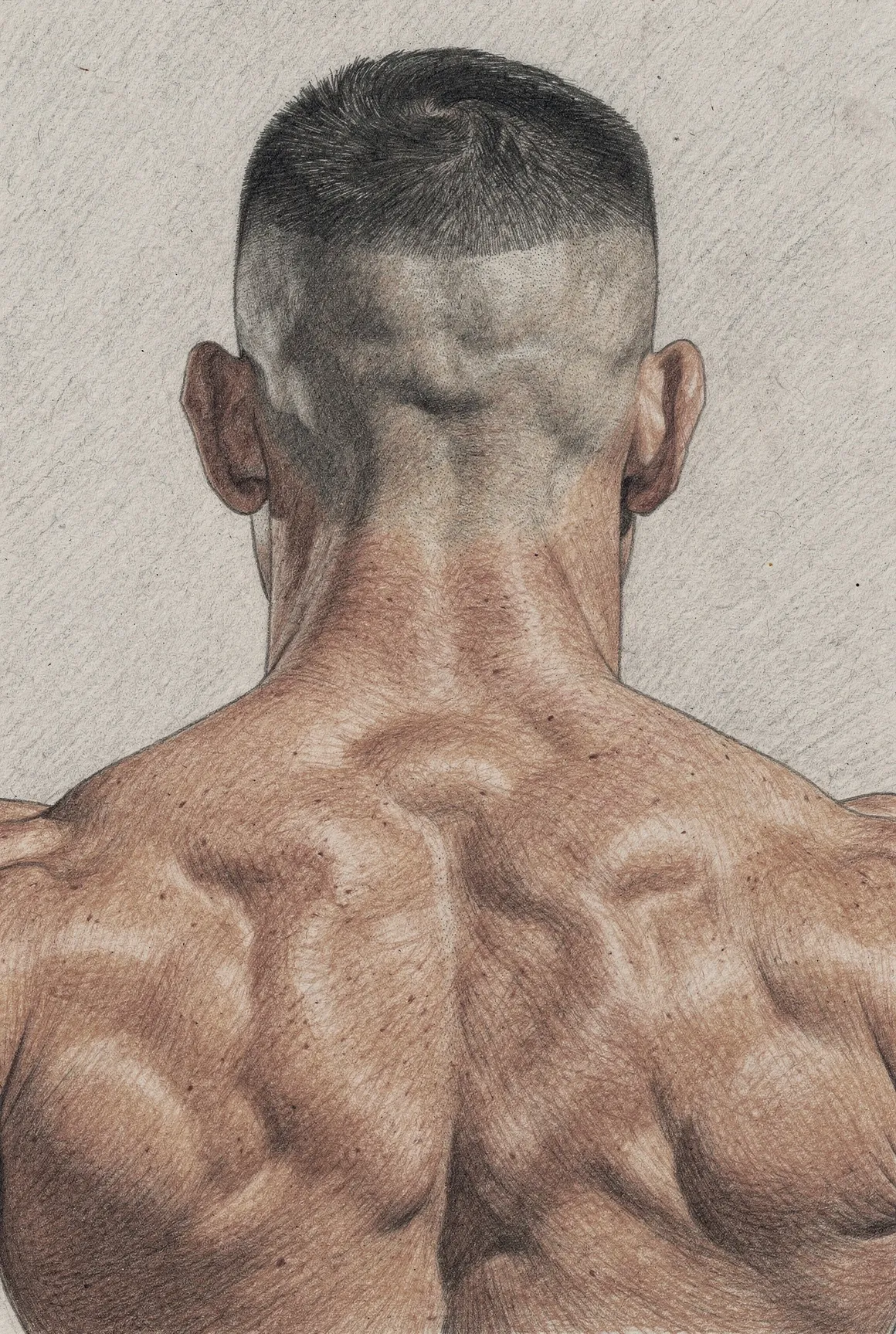

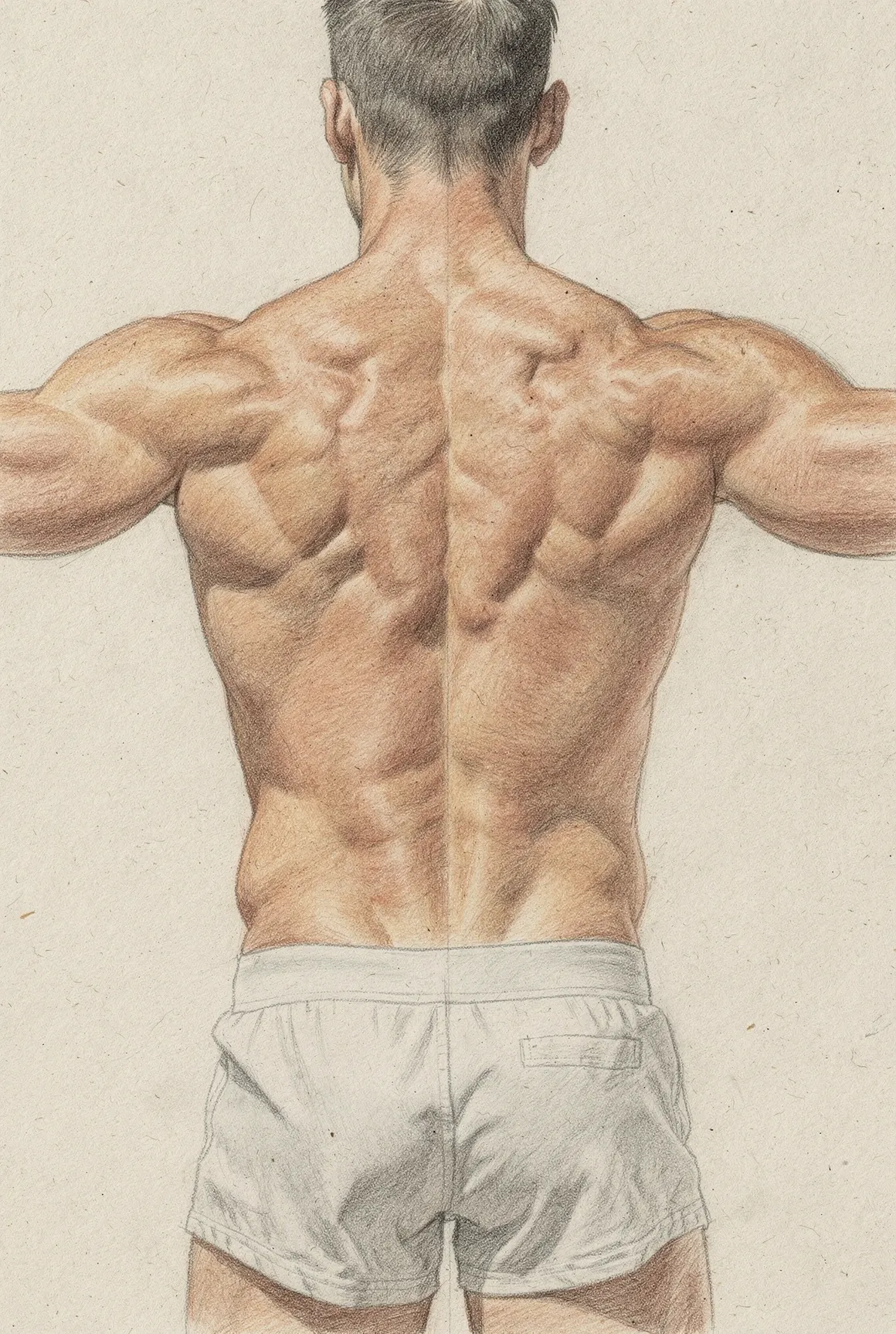

Generated with Flux.2 Pro, these synthographs approach the male body as a physical fact rather than an image. The project steps away from performance, display, or erotic coding and asks a quieter, more literal question: what makes a body feel real? Not beautiful, not idealised, not provocative — but present, weighted, solid, and believable. The figures here are not posed to be admired. They are organised to be trusted. They occupy space, hold themselves upright, and submit to gravity. The body is understood first as matter: roughly sixty percent water, structured by two hundred and six bones, animated and stabilised by more than six hundred muscles. These numbers are not cited to impress, but to remind us that flesh is not symbolic by default. It is built, supported, and sustained.

The work is driven by a fascination with density — not as excess, but as distribution. Density here describes how mass is arranged and borne: how shoulders widen because they must carry load, how the neck thickens to support what sits above and beside it, how the waist narrows as structure resolves into balance. Muscle is present, but never theatrical. Definition follows weight, not the other way around. Contemporary systems of measurement — BMI, lean body mass, body-fat percentage — hover in the background as imperfect attempts to quantify this reality. A dense body may register as overweight; a lean one may appear lighter than it is. Such measurements reveal their limits when faced with structure. These figures are neither cut nor bulked, neither revealed nor concealed. They exist at equilibrium.

The project sits in quiet dialogue with older ideas of the body. Classical proportion, Renaissance anatomy, and the religious notion of the corpus are present as undertones rather than references. In Genesis, Adam is formed from dust and animated by breath. Here, Adam appears not as myth or narrative, but as template: a first body endlessly repeated, adjusted, and reassembled. Drawing-based aesthetics allow the images to behave less like photographs than statements. Faces are secondary and often withheld. Identity is reduced. What remains is structure. The male body has long been eroticised, but here eroticism is incidental. Virility is understood not as invitation, but as capacity. These synthetic bodies do not ask to be desired. They insist on being felt.

Gallery

"I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free." — Michelangelo